SUMBANESE CULTURE

HISTORY

There are now 2 prehistoric relicts in Sumba: In Melolo was found a skeleton of an exceptionally large man and a large clay jug. The items can be seen today in Jakarta. At the finding place near the police station of Melolo is a plaque on it. In Lambanapu on the outskirts of Waingapu were found 5 skeletons and various clay jugs in 2017. Both finds date from the Palaeolithic period between 2800-3500 years ago.

The knowledge of the early history of Sumba is based on stories that were passed down from generation to generation. Only from the 15th century are occasional written records.

According to tradition, the name of Sumba derives from Humba. Rambu or misses Humba was the wife of Umbu or mister Walu Mandoku one of the chiefs among the first tribes who settled in Sumba. He wanted to perpetuate the name of his beloved wife, by naming the island so. They came with ships, landed at the northern tip Tanjung Sasar and founded the village Wunga. The name Humba was applied up do the colonial era. The Dutch named it in their language Soemba.

According to the local religion Marapu, the first human beings came not with ships but via a ladder from heaven to the northern tip Tanjung Sasar and founded the village Wunga.

Anyway, Sumba had always been an isolated island. It was inhabited by several small ethnolinguistic groups. Sumba had its own civilization. There were small clans or kingdoms with their own customs, own social structures and ceremonies during the cycle of life such as birth, marriage and death.

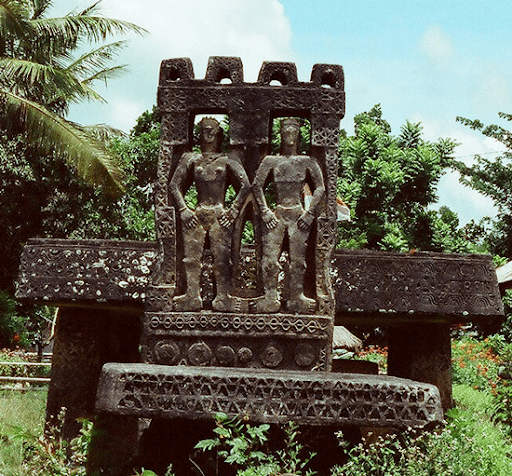

In the fourteenth century, Sumba was part of the Javanese Majapahit dynasty. After this dynasty had collapsed, Sumba came under the rule of Bima in Sumbawa and later Gowa in Sulawesi. These political changes had little impact on daily life in Sumba. Life was more influenced by internal wars between clans and small kingdoms concerning land and trading rights. In these clan wars warriors brought the heads of the killed enemies to their villages and speared them up on so-called skull-trees (Andung) in the middle of the village. They believed that the heads would bring a good harvest and wealth for the village. There were also kidnapping and slavery between villages. Sometimes slaves were sold to neighbouring islands. Because of these wars and attacks, villages were built on hills or mountains and surrounded by stone walls for protection. Despite their hostility, they were economically dependent on each other: the inland villagers grew wood, betel nut, rice, and fruit, while coastal residents made Ikat, wove textiles, produced salt, and operated fishing and trading with other islands. Islands around Sumba regarded Sumba as a very violent island.

Today you can still see skull-trees and sculls near the Rumah Adat in some villages. Today it still happens that Sumbanese burn houses or villages of other ethnic clans or tribes. Within the last years at least 3 traditional Marapu villages have been partly destroyed that way. I heard the story that recently someone cut-out someone’s liver in order to cut-out his soul (which is located there) and ate it.

SUMBA TRADIONAL HOUSES

Traditional houses in Sumba, an island in eastern Indonesia, are known for their unique architecture and deep cultural significance. These houses, known as “uma mbatangu” or “uma ka’u,” are not just places to live but embody the spiritual and social values of the Sumbanese people.

Architecture of Sumba Traditional Houses

- Structure: Sumba houses are typically built on stilts with a thatched roof and walls made from bamboo or woven palm leaves. The roofs often curve upwards at both ends, resembling a boat turned upside down.

- Materials: Bamboo, palm leaves, and sometimes wood are the primary materials used, reflecting the island’s natural resources and climate.

- Stilted Construction: Elevating the house on stilts serves both practical and symbolic purposes. It protects against flooding during the rainy season and keeps the living area cool and ventilated. Symbolically, the elevated position connects the house with the spiritual realm and ancestors.

Philosophy and Cultural Significance

- Ancestral Connection: Sumbanese traditional houses are deeply rooted in ancestor worship and spiritual beliefs. The stilted construction symbolizes a connection between the living and the spiritual world, with ancestors believed to reside in the upper parts of the house.

- Social Hierarchy: The size and complexity of a house often reflect the social status and wealth of its inhabitants. Larger houses are typically owned by noble families or clan leaders, while smaller ones belong to commoners.

- Rituals and Ceremonies: Various rituals and ceremonies, such as births, marriages, and funerals, are conducted within the traditional houses. These events reinforce community bonds and honor ancestral traditions.

- Community Space: Sumba houses are not just residences but also serve as communal gathering places for rituals, meetings, and storytelling. They play a central role in preserving and transmitting cultural heritage across generations.

- Ecological Harmony: The use of natural materials and sustainable building practices in constructing these houses reflects the Sumbanese people’s harmonious relationship with their environment.

Preservation and Challenges

- Modernization: With increasing modernization and urbanization, traditional house-building techniques are at risk of being lost. Efforts to preserve these practices often involve community-led initiatives and cultural education programs.

- Tourism and Awareness: Tourism has provided both opportunities and challenges for preserving Sumba’s cultural heritage. While it raises awareness about traditional houses, it also introduces pressures for commercialization and change.

In conclusion, Sumba traditional houses are more than just architectural marvels; they embody a rich tapestry of cultural beliefs, social organization, and ecological wisdom. Their preservation is crucial not only for maintaining the island’s cultural identity but also for sustaining its unique way of life.

SOCIAL STRUCTURE

The social structure of Sumba, an island in eastern Indonesia, is deeply rooted in traditional beliefs, customs, and hierarchical organization. Here’s an overview of the social structure and key elements that define it:

1. Clan System:

- Clan Identity: Sumbanese society is organized into clans or “kabisu” that trace their ancestry through patrilineal lines. Clans play a crucial role in social organization, determining roles, responsibilities, and social status within the community.

- Hierarchy: Clans are often ranked hierarchically based on historical prestige, wealth, and influence. Higher-ranking clans typically hold more power and authority in decision-making processes.

2. Caste-like System:

- Nobility (Raja and Marapu): At the apex of Sumbanese society are the nobles or “raja” who are considered semi-divine and hold significant spiritual and temporal authority. They are believed to be descendants of the gods and are responsible for upholding traditional laws and rituals related to the animistic Marapu religion.

- Commoners (Ata and Maramba): Below the nobility are commoners, categorized into two main groups:

- Ata: Free commoners who work the land and engage in various occupations.

- Maramba: Slaves or servants who historically were bound to noble families but could earn freedom through various means.

3. Inheritance and Wealth Distribution:

- Primogeniture: The inheritance of property and titles typically follows a system of primogeniture, where the eldest son inherits the bulk of the family estate and assumes leadership roles within the clan.

- Land Ownership: Land ownership is crucial in Sumbanese society, with land often inherited and passed down within clans. It serves as a measure of wealth and status.

4. Social Customs and Traditions:

- Adat: Traditional customs and laws, known as “adat,” govern various aspects of life including marriage, land rights, and communal responsibilities. Adat is deeply respected and upheld as a way to maintain social order and harmony.

- Rituals and Ceremonies: Important life events such as births, marriages, and funerals are marked by elaborate rituals that reinforce social bonds and cultural identity.

5. Contemporary Influences and Challenges:

- Modernization: The influx of modern influences, education, and urbanization is gradually altering traditional social structures and roles.

- Tourism: Tourism has brought economic opportunities but also challenges to preserving traditional practices and maintaining cultural integrity.

- Government Policies: Indonesian national laws sometimes conflict with traditional customs, leading to ongoing negotiations and adaptations within Sumbanese society.

In essence, the social structure of Sumba reflects a blend of spiritual beliefs, hierarchical organization, and community cohesion centered around clans and traditional practices. It continues to evolve amidst changing external influences, posing both challenges and opportunities for its preservation and adaptation.

MARAPU BELIEVE

Marapu is the traditional religion of the Sumbanese people, and it is deeply intertwined with their cultural practices, social structure, and worldview. Here’s an overview of the beliefs and concepts central to Marapu:

1. Cosmology and Beliefs:

- Ancestral Worship: Central to Marapu is the belief in ancestral spirits (“Marapu”), who are revered and considered guardians and protectors of the community. Ancestors are believed to have a continuing influence on the living, guiding and shaping their lives.

- Dualistic Cosmology: Marapu cosmology often includes a dualistic worldview, with the world divided into the visible realm (where humans reside) and the invisible realm (inhabited by spirits and ancestors). This dualism shapes rituals and beliefs around maintaining balance and harmony between these realms.

2. Spiritual Practices and Rituals:

- Offerings and Sacrifices: Rituals in Marapu involve offerings and sacrifices to appease and honor ancestral spirits. These rituals are crucial for seeking blessings, protection, and guidance from the spiritual realm.

- Divination and Shamanism: Shamans or spiritual leaders (“dukun”) play a significant role in Marapu rituals, acting as intermediaries between the human and spirit worlds. They perform divination to communicate with spirits and provide guidance on various matters.

3. Social and Cultural Significance:

- Community Cohesion: Marapu beliefs foster strong community bonds and social cohesion, as rituals and ceremonies often involve collective participation. They reinforce shared values, norms, and identity within the community.

- Life Cycle Rituals: Important life events such as birth, marriage, and death are marked by elaborate rituals and ceremonies rooted in Marapu beliefs. These rituals not only celebrate milestones but also ensure continuity and harmony within the community.

4. Adaptation and Preservation:

- Integration with Modern Influences: Despite modernization and the spread of other religions, Marapu continues to be practiced and adapted by many Sumbanese people. It coexists alongside Christianity, Islam, and other faiths, showcasing its resilience and adaptability.

- Challenges: The preservation of Marapu faces challenges such as changing lifestyles, migration, and environmental pressures. Efforts to document and revitalize traditional practices are ongoing to ensure the continuity of Marapu beliefs and rituals.

5. Sacred Sites and Symbols:

- Sacred Sites: Certain natural landmarks and ancestral graves are considered sacred in Marapu belief, serving as places of spiritual significance and pilgrimage.

- Symbolism: Symbols such as sacred trees, stones, and artifacts hold deep symbolic meaning in Marapu rituals and ceremonies, connecting the physical and spiritual realms.

In conclusion, Marapu belief system is not just a religion but a comprehensive worldview that shapes the cultural identity and social fabric of the Sumbanese people. It reflects their deep reverence for ancestors, their harmonious relationship with nature, and their collective responsibility towards maintaining spiritual balance and well-being.

IKAT

Ikat weaving in Sumba is a revered tradition that holds deep cultural and social significance within the community. Here’s a detailed exploration of Sumba ikat weaving:

1. Traditional Techniques:

- Ikat Process: Ikat is a resist-dyeing technique where threads are tightly bound in sections before dyeing to create patterns. The bindings resist the dye, resulting in intricate designs when woven. This process requires skill and precision to align patterns accurately.

- Natural Materials: Traditionally, Sumbanese weavers use natural materials such as cotton or local fibers for the yarns. Natural dyes derived from plants, roots, and minerals are often used to achieve vibrant colors like red, indigo blue, and yellow.

2. Cultural Significance:

- Symbolism: Ikat textiles in Sumba are rich in symbolism, often incorporating motifs that represent aspects of nature, mythology, clan lineage, and spiritual beliefs. These motifs can vary across regions and clans, serving as visual markers of identity and social status.

- Ritual and Ceremony: Ikat textiles play a central role in Sumbanese rituals and ceremonies, including births, marriages, funerals, and traditional festivals. They are worn as ceremonial attire, used as offerings to ancestors, and exchanged as gifts to strengthen social bonds.

3. Regional Styles and Variations:

- Distinct Styles: Different regions of Sumba have their own distinctive styles of ikat weaving, characterized by unique patterns, color combinations, and weaving techniques. For example, East Sumba is known for its intricate geometric designs, while West Sumba may feature more stylized motifs inspired by nature.

- Collaborative Efforts: While men traditionally weave ikat textiles in Sumba, it often involves collaboration with women who prepare the yarns, dye the threads, and assist in the weaving process. This collaborative effort reinforces community ties and knowledge sharing.

4. Contemporary Context:

- Revitalization Efforts: In recent years, there has been a concerted effort to preserve and promote Sumba’s traditional ikat weaving techniques. Initiatives include workshops, educational programs, and support for local weavers to sustain their craft and livelihoods.

- Market Demand: Sumba ikat textiles are increasingly valued in global markets for their craftsmanship, cultural authenticity, and unique designs. This has created economic opportunities for Sumbanese weavers while raising awareness about the importance of preserving indigenous weaving traditions.

5. Challenges and Sustainability:

- Modern Influences: Globalization, changing lifestyles, and economic pressures pose challenges to the sustainability of traditional ikat weaving practices in Sumba. Efforts are needed to balance tradition with contemporary demands and ensure the transmission of knowledge to future generations.

- Cultural Heritage: Recognizing the cultural significance of Sumba ikat weaving as intangible cultural heritage is essential for safeguarding its authenticity and continuity amidst evolving social and economic landscapes.

In conclusion, Sumba ikat weaving is not just a textile craft but a cultural expression that embodies the artistic creativity, social identity, and spiritual beliefs of the Sumbanese people. Its preservation and promotion are crucial for maintaining cultural diversity and sustaining livelihoods in the region.